WASHINGTON — NASA has added another asteroid flyby to its Lucy mission later this year that will provide a test of its capabilities for future encounters.

NASA announced Jan. 25 that the spacecraft will fly by the small main-belt asteroid 1999 VD57 on Nov. 1. The project selected that asteroid after one scientist collaborating on the mission, Raphael Marschall of France’s Nice Observatory, compared the spacecraft’s trajectory to the orbits of 500,000 asteroids.

Lucy’s current trajectory will take the spacecraft as close at 64,000 kilometers to the asteroid. The spacecraft will perform a series of maneuvers starting in May to adjust its trajectory so that it will instead pass 450 kilometers from the asteroid.

Hal Levison, principal investigator for Lucy at the Southwest Research Institute, said at a Jan. 25 meeting of NASA’s Small Bodies Assessment Group that the mission team has given 1999 VD57 the provisional name of Dinkinesh. That is the Ethiopian name for the Lucy fossil after which the NASA mission is named. The name is pending formal approval by the International Astronomical Union.

Dinkinesh is a S-type asteroid, he said, with a diameter of no more than 800 meters and comparable in size to Bennu, the near Earth asteroid visited by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission. It would be the smallest main-belt asteroid that a spacecraft has flown by.

While the flyby will collect images and other data about the asteroid, that is not the primary reason for the close approach. “This is a risk mitigation exercise,” Levison said, focusing on the “terminal tracking system” the spacecraft will use to lock on to the asteroid as it approaches, maximizing the data its instruments collect.

That system has some heritage from past missions but has never been tested in space before. “We decided that it is beneficial to test it out as soon as we can,” he said.

The flyby of Dinkinesh is in addition to another main-belt asteroid, 52246 Donaldjohanson, that it will fly by in 2025. Lucy will then fly by several Trojan asteroids at Jupiter’s distance from the sun between 2027 and 2033.

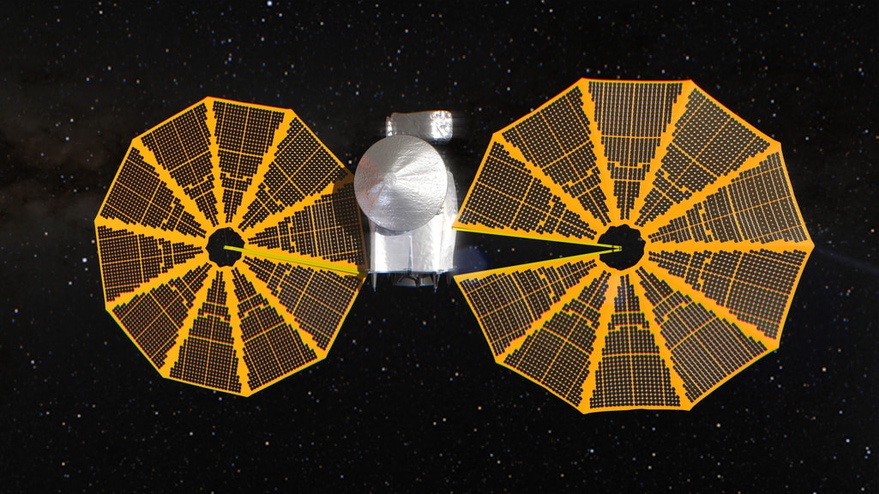

The Dinkinesh flyby will also test how well it can point at a target given that one of its two large circular solar arrays has not latched into place. “We’re not exactly sure, given that the solar array is not latched, of the pointing stability characteristics of the spacecraft, so this will also help us determine that,” he said.

NASA announced Jan. 19 that it was suspending efforts to fully deploy that solar array after the most recent deployment attempt in December showed only “minimal levels” of progress. The array, the agency said, was nearly fully deployed and appeared to be stable, but did not rule out additional efforts to lock it into place late next year, when the spacecraft makes another Earth flyby.

Levison said that, in the December attempt, there were signs that the array was tensioning, which he said was a positive sign. “It makes us really quite confident that it is safe to fly the mission as-is,” he said.

Related

ncG1vNJzZmiroJawprrEsKpnm5%2BifK%2Bt0ppkmpyUqHqiv9OeqaihlGKzrcXBsmStp12hwqTFjKagrKuZpLtw